Provocative, amusing, informative and feminist

Up Byron Bay way, Mandy Nolan is a public institution of sorts, due to her weekly Soapbox column in the Byron Echo. In her own words, she is “like the big prawn: colloquial, parochial but strangely imposing”.

A self-proclaimed expert on all matters feminine, her resume is broad but each of her income generating pursuits are infused with humour, whether it is on stage as a stand-up comic, authoring her four books, writing for Mamamia, giving keynote speeches, appearing on Q&A, teaching comedy at Byron Community College or writing a satirical and provocative ‘Dear Tourist’ letter to the Northern Star, about how too many tourists were impacting on the lives of Byron Bay’s ordinary citizens.

Signed, Love, The Community, the letter canvassed many issues, including this comment: “Anyway most of our parks are where our homeless have to live. Because see those houses you are staying in? Most of them were supposed to be our homes.”

As expected, Nolan’s view attracted both bilious and supportive responses: “Oh, ok, you go around and tell all the local small business owners you don’t want tourists there anymore.” “I agree with her entirely. As someone who was born in Byron, the place sucks now.”

Nolan created Stand UP for Dementia, too, a peer reviewed humour therapy for people with dementia and the subject of her TED talk. And, amid all of her comedic pursuits, she mothered five children, whom she says are the “true source of my creativity; when I had kids, everything else looked easy”.

Geoff Helisma digs a little deeper into the Mandy Nolan persona, although in reality there’s not all that much to uncover. Thirty-four years of exposing herself to the public in the name of comedy has seen to that.

Says Mandy Nolan: “Comedienne is one of those weird words that tell you what sex [and profession] a person is, as if it is going to make difference, but she’s not a doctor she’s a ‘doctorienne’. I’ve always said a comedian is a funny person with a vagina.”

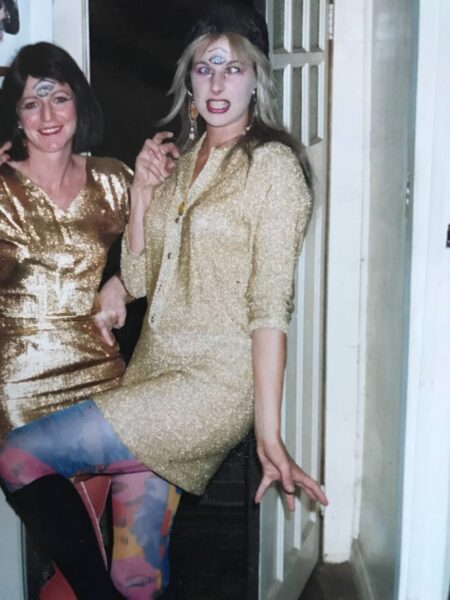

Nolan’s initial foray into the world of comedy was somewhat accidental, which she says, as a 17-year-old, was germinated during an era renowned for “shoulder pads and big hair”.

“I was studying journalism at Queensland University in 1985 and I got involved in a university show. I really enjoyed the freedom to get up and do comedy about issues happening at the time. I started out performing to a predominantly feminist crowd, who thought I was amazing. Then I got booked straight away to do all of these gigs. Then I walked into a room where it wasn’t a feminist crowd and they hated me.”

The memory triggers a brief burst of laughter. “I learnt a lot,” she says, “I was very much in that 1985 academic niche: I was a real lefty, it was Queensland and I was going to anti Joe Bjelke Peterson rallies every weekend, which is funny because I grew up in [Peterson’s home town] Kingaroy. It was a very, very politicised time in Queensland. It was quite an exciting time to find your voice.

“To tell you the truth, I wasn’t very good, but I didn’t know it. It took about 10 years to become an average comedian. It’s like playing piano: you’ve got to have your [practice] time up; you’re not a good pilot after 10 hours … but after 1,000 hours?

“I think people forget how important it is to persist with something that you really want to do. Sometimes you have to do it for a long time before you get good. There is no instant self-gratification.”

Like many performers, Nolan is empowered when she takes to the stage. “There is no greater joy for me than walking into a room with nothing more than a microphone and my ability to tell a story and relate to people – I can give them an hour of their time that is a great time. I just love the ability to create something out of nothing out of everyday experiences and the way we see life.

“In the last ten years I have become the comedian I hoped to become, while thinking I’d never be able to do it. It did not come naturally; it came through perseverance, hard work and, you know, a lot of times not doing a great show but not giving up.”

But it hasn’t all been plain sailing; Nolan’s perseverance was tested early in her career. “I walked on stage and there were about 500 people at a university refectory. The first thing someone yelled out was – you can’t really print this – ‘Show us your c*%t!’

“And I thought, ‘Oh my god!’ and said, ‘Well, show us your c#*k!’ What a stupid thing to say. Then this guy ran up and pulled his pants down right in front of me. Then someone cracked a beer on his head and he collapsed. And then it just turned into a fight, [but] I just did my routine, got my thirty bucks and went home. Or twenty bucks … it might have only been ten bucks.

“When I got home, I remember thinking, ‘Wow! I feel so free! That was such a violent gig, so terrifying.’ Pants were down, there were chairs flying … it was like being in the Wild West, [but] I’m still here. They hated me, but what could happen after that? I felt bullet proof.”

As a country girl raised in Kingaroy, a town renowned as the ‘Peanut Capital of Australia’ and for its ultra conservative prodigy, then Queensland premier Joh Bjelke Peterson (1968-1987), Nolan moved to Brisbane to study sociology where, ironically, she was also working for a modelling agency.

“It was funny; feminism certainly hadn’t hit Kingaroy. I started reading some academic books, [like] The Female Eunuch and Simone de Beauvoir: the whole idea of nature and nurture and the idea that gender wasn’t inherent, that our concept of what it was to be feminine was manufactured, just as being masculine had.

“That was a revelation to me and such a freeing up. Having an experience part-time in the modelling industry, I could see that it was quite awful (chuckle), you know, being valued just for what you look like. That was when I embraced the whole idea of women needing to find their voice and push on beyond just being decorative items.”

Times have changed since those days, though, and the classical definition of feminism – the advocacy of women’s rights on the ground of the equality of the sexes – has had many facets added to its edifice.

Arguably, the concept started in the UK in 1839, when women were first given custody rights over their children. The second feminist ‘wave’ – campaigning for legal and social equality – rolled from the 1960s through to about 1990. The third wave’s genesis is widely attributed to the ‘riot grrrl’ punk band movement, which started in Olympia, Washington, USA in October, 1990. The groups addressed issues such as rape, domestic abuse, sexuality, racism, patriarchy, and female empowerment.

Come the mid ’90s, The Spice Girls co-opted the concept, introducing the idea of ‘Girl Power’ to combat stereotypical views of feminism. “It’s about labelling,” said Spice Girl Geri Halliwell. “For me feminism is bra-burning lesbianism. It’s very unglamorous. I’d like to see it rebranded [as] a celebration of our femininity and softness.”

The fourth wave is thought to have started in 2012 and is often associated with the use of social media and campaigns to achieve justice for women while opposing sexual harassment and violence against women. While the above précis of feminism’s history is rather slim, perhaps bordering on superficial, its commercial exploitation adds to the confusion.

Nolan laughs when asked: And then there are the spin-offs: for example, nastygal.com sells what it calls a Girrl Power bodysuit, described thus: the Girrrl Power Bodysuit features a wrap design, leopard print, V-neckline with ruffle detailing, tie detailing at sleeves, solid panty, snap closures at crotch, and medium bottom coverage’. Isn’t that some sort of oxymoronic juxtaposition of what feminism fought against, but now, ostensibly, has embraced and, as a result, is being exploited commercially?

“There are many types of feminism now,” she says. “I don’t prescribe to what I refer to as ‘Choice Feminism’. That’s sort of ‘I can choose to do that’, but I think you need to investigate the social context of how those choices are made – no choice is made in isolation. Choosing to objectify yourself, because you’re in control of the objectification, doesn’t mean you’re in power. It just means that you are doing your own subjugation (laughs).

“For me, feminism can be very individual. I think both men and women have been ripped off by the masculine and feminine stirrer types who are pervasive. I think, now, the whole gender conversation is quite exciting. No matter what people think, it just allows people the space to be who they are without, kind of, being bullied into feeling not great about themselves. That whole hyper masculine, hyper feminine stereotype has a lot to answer for, for people feeling they are never enough.

“Capitalism loves that – it’s much easier to market to people who don’t like themselves than it is to people who think, ‘You know what? I am okay.’ People who think they are okay don’t buy as much.”

Nolan says she’s not a hardline feminist. “I’m a hypocritical feminist, that’s probably what I would call myself. What I like the most is that people are being made accountable for their behaviour via the #MeToo movement for example.”

However, feminism was a key motivator from the very beginning. “There weren’t a lot of woman role models to look at [in 1985], to know what it looked like to be a female comedian.

“Like, there was I Love Lucy, Wendy Harmer was starting out, but [at the time] I didn’t really want to be a comedian, I just liked performing. I kept at it because I enjoyed it. While I was pretty average I just kept going. I wanted to be an actor, but I’m terrible at acting. So I just kept myself performing and then, bit by bit, one day I looked around and went, ‘Wow, I’m actually living off my comedy, I’m getting so much work. I must be a comedian.’

“That was a surprise, so it is an accident; it’s an accidental career. I didn’t call myself a comedian until I’d been doing it for over fifteen years, because I would have felt like a poser to claim a title like that.”

Nolan thinks of herself as “a good comedy evangelist”, which she says is a way of challenging herself “to make an audience like me, because there’s no point in doing my comedy to people who agree with me”.

“My politics, my point of view and how I see the world; how do I get that across to an audience who may not share the same values and experiences as me? How do I get them to embrace and connect with those ideas?

“Comedy is powerful for that; it’s a great leveller, and connector, because you are laughing at yourself; pointing the finger at yourself. Deep down, when you talk to people, it doesn’t matter what side of the fence their politics is, left or right. Deep down, most people share the same values about what they believe a fair go is. They naturally see a bullshit alert. Most people have a pretty good idea of what they think is right or wrong.”

Nolan has come a long way from when she first ventured into the comedic realm, a long way from telling a joke about her first period in which she failed to hammer a tampon up her vagina with a rock.

“In retrospect,” she says, “people didn’t really want to talk about that in a general way, but I thought it was actually a very funny piece of material. It was clearly a bit confronting, but…”