John McNamara, Research Officer, Port of Yamba Historical Society

When the colony was founded in 1788, the North Coast was hardly an unknown quantity. Captain Cook passed by in May 1770. He named Cape Byron and Mount Warning but sailed past the Clarence entrance at night.

Twenty-nine years later, Lieutenant Matthew Flinders did not do much better – and in daylight. Governor Hunter in 1799 sent Lieutenant Flinders north to examine the coast “with as much accuracy as the limited time of six weeks would permit.”

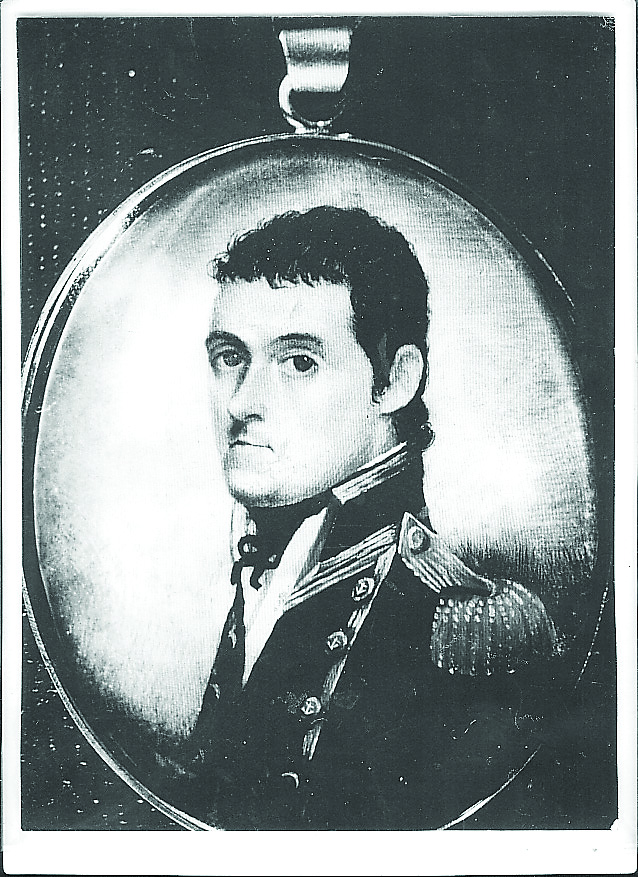

Lieutenant Matthew Flinders (1771-1814)

Flinders, his crew of eight and an Aborigine, Bongaree, sailed from Sydney on July 8, 1799, in the 25-ton sloop Norfolk. They anchored at dusk on July 11 in the entrance to a “wide shoal bay” in two and a half fathoms. Next morning Flinders took a boat party to the northern headland before returning to the sloop and going ashore on the southern headland, making him and his crew the first Europeans to set foot on the future site of Yamba. Here, he inspected Aborigines’ huts, took his noon observations with a sextant, filled casks from a spring in the hillside (identified in Harbour Street by a Port of Yamba Historical Society marker in 1982) and sailed away.

His journal entry read: “The sloop had sprung a bad leak, and I wished to have her laid on shore, but not finding a convenient place, nor anything of particular interest to detain me longer, we sailed at one o’clock when the tide began to rise.”

He also acknowledged his disappointment at “not being able to penetrate into the interior of New South Wales by any opening examined in his expedition”, and went on to claim as an ascertained fact that no river of any importance intersected the east coast between the 24th and 39th degrees of south latitude

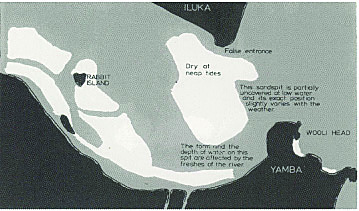

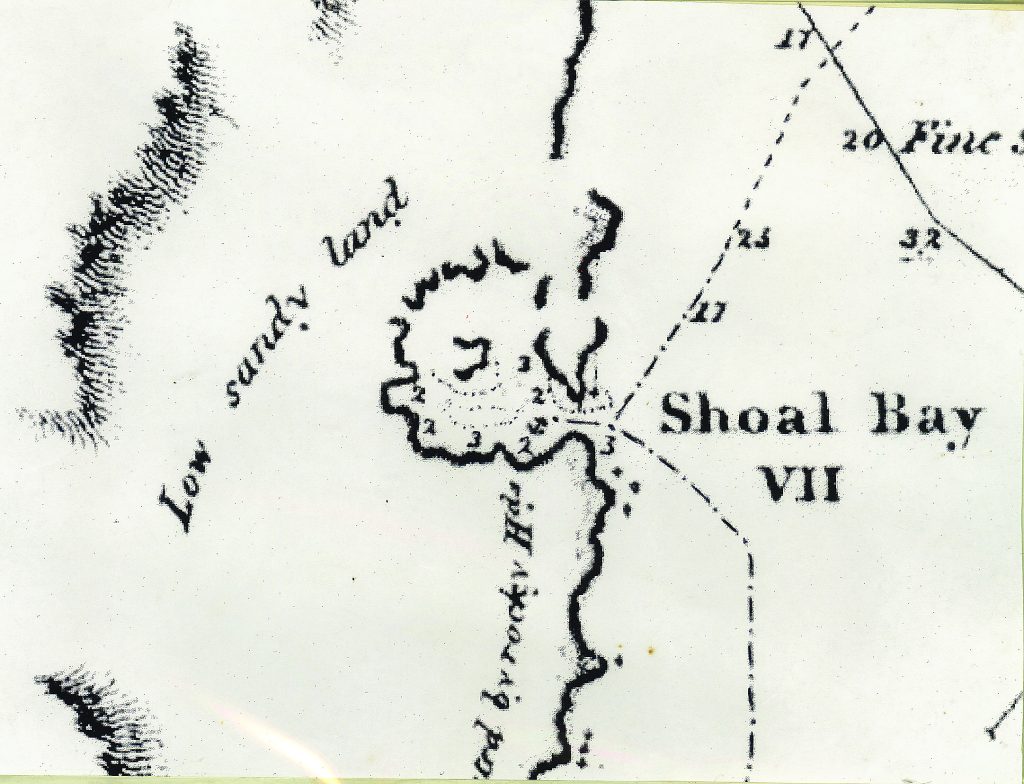

The entrance to “Shoal Bay” as surveyed by James Burnett in 1845. Probably as Flinders would have found it, a width of about 6800 feet, the channel being described as filled with sandbanks, through which the river found its way to the sea, by numerous small channels too tortuous and shallow to be navigable unless by the smallest of coasters except along the southern shoreline.

Flinders was not impressed by the stretch of water he dismissed as Shoal Bay, although as evidenced by his plan of the entrance to the “Bay” and where soundings were taken, he did not venture upstream at all. Because of the huge sand spit which projected across the entrance from the north, he believed his anchorage was a small inlet in a landlocked bay. In the words of noted Grafton historian, Mr. Robert Craigie Law, Flinders was very careless. Mr. Law said “he should have known, by the ebb and flow of the tide, that there was a large body of water behind the bay. The existence of the bar was another of many factors which should have indicated the presence of a river.”

Flinders map of Shoal Bay showing location of sounding depths

However, Flinders did not realise he had anchored where the biggest river on the coast entered the sea. Botanist, Allan Cunningham, read the evidence better from near where the river begins. In 1826, on an expedition from the Hunter River to Moreton Bay via New England, he wrote from near Tenterfield: “From the formation of the country, I imagine there is a large river in this direction emptying into Shoal Bay.” Governor Darling was anxious to explore this region from the east and on 14 August 1828, the Rainbow under the command of Henry Rous headed north from Sydney. On the morning of the sixth day of the voyage, “the mouth of a large river” was sighted “apparently running in a N.N.W direction”. The pinnace was “sent to sound for an entrance” but without success “from the surf breaking on the bar”. He continued northwards and the Big River again went undetected.

Richard Craig

Richard Craig is generally regarded as the discoverer of the Clarence. He was born in 1812 in County Longford, Ireland and came to Australia as a free man accompanying his father, William, on the Prince Regent, after the latter was convicted of sheep stealing and transported, arriving in Sydney on 09 January 1821. A 16-year-old apprentice stonemason, he and his father were convicted of cattle stealing in 1828. Richard was sentenced in Sydney to seven years hard labour in chains at the penal settlement of Moreton Bay arriving on the City of Edinburgh on 10 January 1929 and William was sent to Norfolk Island where he died on 24 December 1836.

Richard made his third (and only successful) escape on 17 December 1830 and slowly made his way down the coast, spending considerable time with another runaway, Sheik “Black Jack” Brown and Kumbangerie Aborigines. He finally reached Port Macquarie on 04 August 1831 and surrendered to the authorities. Meanwhile, a herd of 74 cattle and 4 horses were dispatched from Bathurst to Port Macquarie on 03 February 1831 but were abandoned in the bush. Craig offered his services to search for them and using his knowledge of the bush and Aboriginal contacts found 57 of the cattle and 2 of the horses on 25 November. He was awarded by being allowed to remain at Port Macquarie for the remainder of his sentence.

Sheik Brown surrendered at Port Macquarie in 1832 after 3 years and 4 months in the bush, chiefly residing with Aborigines at the “Big River” and its neighbourhood, describing it to authorities as “(he gave) a very promising statement of the navigation of the river, which abounds with fish – the land excellent – abundance of emu, kangaroo and wild fowl are in all directions in this river. Fine oak, gum and other trees of use, for various purposes are growing there.”

The natives called the river Brimbo or Berin. Lower Clarence Aborigines called the river (depending on how different people who heard the word spelt it) Berrinbah, Booryimba or Breimba. Sheik could only have discovered the name from the Aborigines of the area. Yaegl and Gumbaingirr people travelled and camped across the whole of the rich environment between the Clarence River and the coast.

Richard Craig was discharged from the Port Macquarie Convict establishment on 30 September 1835 and made his way to Sydney where he gave information concerning the Big River to Thomas Page, Chief Clerk to the Superintendent of Convicts at Hyde Park. Page was also brother-in-law of Francis Girard, businessman and timber merchant on the Macleay River to whom he no doubt passed the information on.

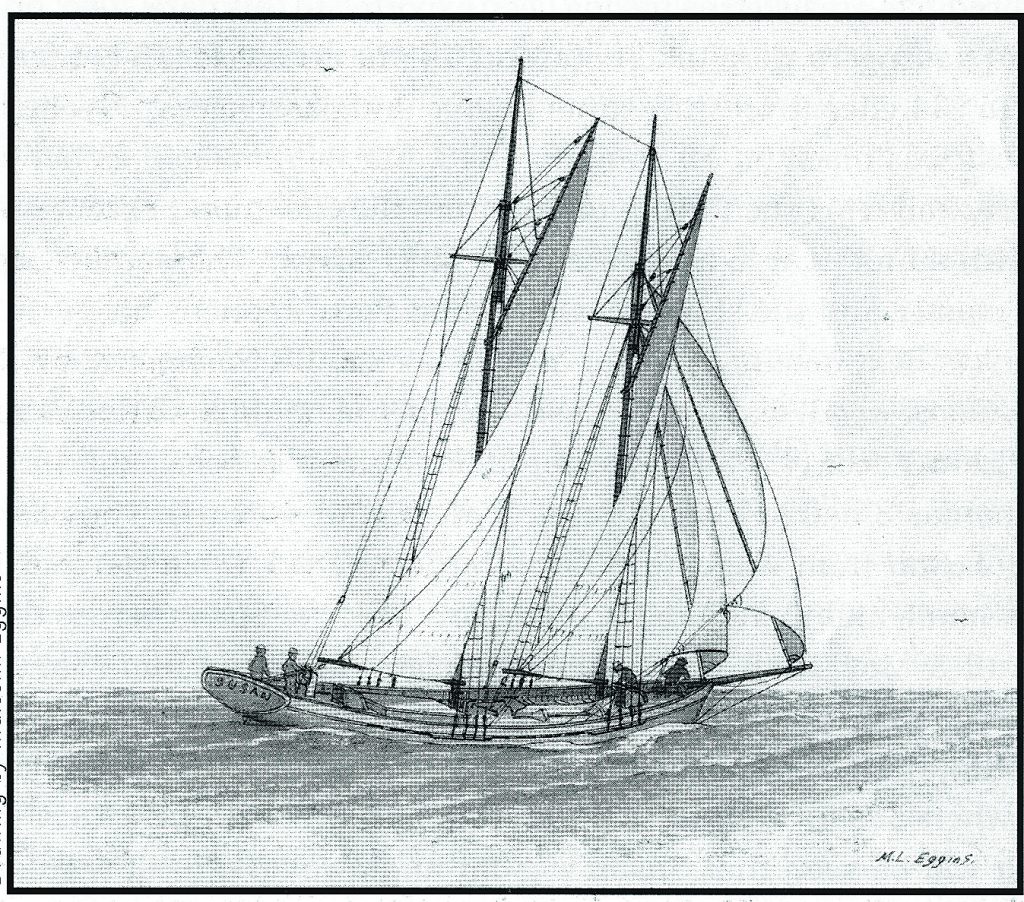

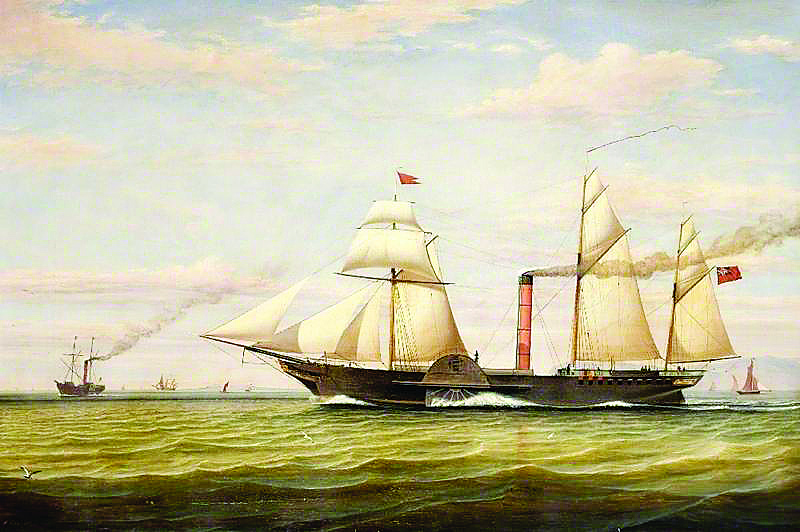

Sketch of the Susan by the late Malcolm Eggins of Grafton

Craig worked in the timber yard of Thomas Small and his associate, Henry Gillett, timber merchants of Kissing Point, who decided to act on his report of large stands of timber at the Big River by sending his 52-ton schooner Susan, commanded by Harry Thorne, about April 1838. However, the bar at the mouth of the river was found to be too rough so they proceeded to Moreton Bay for water but again baulked at the dangerous sandbar on the return journey.

The Sydney Monitor newspaper reported that on 01 May 1838, the Susan sailed from Sydney with John Small (representing his brother Thomas), Henry Gillett and 12 pairs of sawyers to cut cedar at the Big River. One of the sawyers was Steve King who remained on the Clarence until 1842. King’s Creek and King Island near Lawrence were named after him. John Kellick, another timber merchant, also sent his small cutter Elizabeth and the two vessels met outside the river bar before proceeding upriver. The Susan was reportedly the first vessel to enter the Big River, and it brought the first load of timber from the Clarence in early July 1838, leaving the sawyers behind.

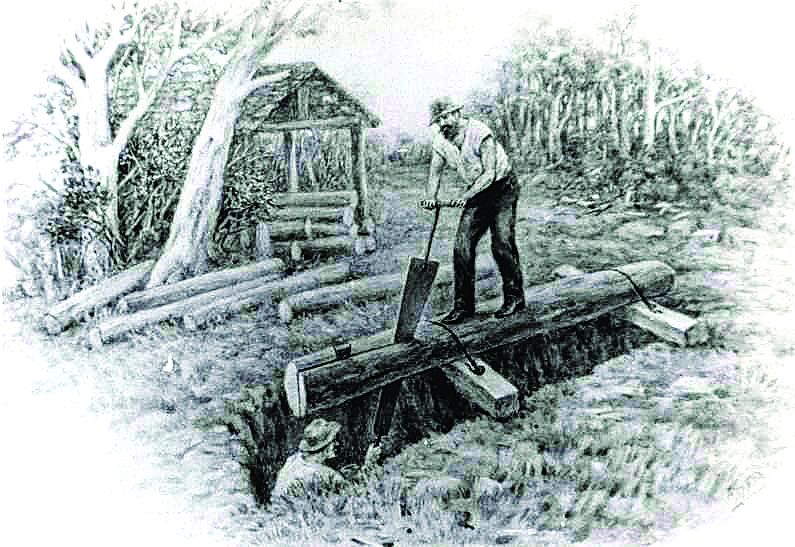

After felling a tree, the log was positioned over a sawpit the timber was sawed with a long two-handled saw, usually a whipsaw, by two people, one standing above the timber and the other below, often standing in water and sawdust up to his knees. It was used for producing sawn planks from tree trunks, which could then be cut down into boards, pales, posts, etc

Sawpit

Meanwhile on 11 May, Francis Girard dispatched his ship Taree from Sydney, collecting a party of sawyers at the Macleay on the way but arrived after the other two ships. On board was Robert Henry Madocks, a clerk at Girard’s Steam and Sawmill establishment at Darling Harbour, who drew the first map of the river as they proceeded upstream. It is quite an accurate map of the river to the limit of navigation, considering the method of preparation, and shows Woodford Island (yet to be named), Susan and Elizabeth Islands, side rivers and streams and Phillip’s boat building yards at “The Settlement”, later renamed South Grafton.

About December 1838, Girard sent Captain James Butcher in charge of his vessel Eliza to the Big River. He took field notes using compass and estimated distances as he proceeded upstream. Upon his return to Sydney, Draftsman, James Warner of the Surveyor General’s Office, using those notes, drew a plan of the river. Unlike Madocks, he ignored Woodford Island, introduced several bends in the river which do not exist and the only detail apart from indicating abundant millable timber is the location of the logging camps of John Kellick, Francis Girard, Thomas Caffrey and Sorrell in the present day Copmanhurst area. It would appear that Butcher’s aim was to produce a map to allow ensuing ships to locate the camps.

And so, the Clarence River District became populated even though the majority was described by later settlers as ‘drunken troublemaking sawyers who stirred up the Aboriginals’. They were a law unto themselves and although a few had brought their families to the Clarence, most were single. Many had been convicts who had served their time, but there were also runaways from Moreton Bay who were working as ‘mates’ to sawyers.

Typical Paddle Steamer in the mid-1800s

The influx of squatters to the district was triggered by a pastoralist, Joseph Hickey Grose, who decided to check out its potential by sending his steamer, King William, on 20 May 1839 under Captain F Griffin. On board were Deputy Surveyor-General Samuel Augustus Perry and several potential timber cutters, squatters and investors who paid £10 per ticket. Perry wrote a glowing report on the qualities of the land and timber supplies and was soon followed by settlers and stock both by ship and overland from Falconer Station near Guyra along what became known as Craig’s Line.

In November 1839, the Big River was renamed the “Clarence” in honour of King William IV, the Duke of Clarence.

The Squatting Act of 1839 entitled “An Act to further restrain the unauthorized occupation of Crown Lands and to provide the means of defraying the expense of a Border Police” (Act 2 Vict. No 27)” provided for the taking out of grazing leases for £10 per annum plus an assessment charge of one half-penny per head of horned cattle and threepence per head for horse. The aim of the Border Police was to protect expanding colonists and their landholdings, while at the same time to attempt to “conciliate” the Aboriginal people, minimising the involvement of armed settlers.

John Small is credited with being the first pastoralist on the Lower Clarence, in particular by his decision to bring in horned cattle and horses. He and his son, John Frederick Small, managed to build on the first 700 acres on Woodford Island in 1839. He was followed closely by Francois Girard, through his local manager William Williams, who took up the property “Waterview”. Part of that property is still identified today by the Waterview Heights area of South Grafton. Many other large pastoral properties ensued.

By 1840, the Clarence had been included in the “settled lands” where people were permitted to take up tenure. This involved the land on

either bank of the river, two miles in width and upstream at least 10 miles from the head of navigation at Woolport, as Grafton was then known. Development of the squatting runs and the shipping particularly of wool and timber, led to the formation of villages and a demand for town lands.