Hugh Murphy (1894 – 1994) was born at Palmers Island and passed away just days after his 100th birthday, which was marked by a military police escort to a celebratory mass and birthday party attended by more than 200 people.

He served on the front lines throughout WW1, including all of the Gallipoli campaign. Donna Morgan, who was 22 when Hugh died, tells his story from a granddaughter’s perspective. My grandfather, Hugh Murphy (Pa), was born in 1894 at Palmers Island on the Clarence River in NSW. He was the son of Irish-born Patrick Murphy, who had migrated to Australia about 20 years prior, and Rosanna Nolan, who was born in Maitland. Hugh was their eighth child.

At the age of 12, after school, Pa was offsider to his father and two brothers, working the ferries around Palmers Island. At 13 years of age, he worked full time (7 days a week) on a local farm at Mororo for about seven months, before being asked to work at Mr. Perkin’s bakery shop at Yamba. For four years his daily duties included baking up to 600 loaves of bread and then spending eight hours delivering them around Yamba and lower Palmer’s Island in a horse and cart. Although he worked 14-hour days, Pa loved it and said he “felt like King Edward VII driving around the district in a horse and cart”.

Yearning for adventure, he set off for the Big Smoke in Brisbane in 1911, where he worked as a porter at Roma Street railway station for 12 months, before heading to Bundaberg where he spent a season cutting cane. Returning home, Mr. Perkins gave him his old job back … and it was here that Pa heard the news that Britain (and therefore Australia) had entered the war on August 4, 1914.

Hugh enlisted in Grafton on September 19, 1914. His older brother, Patrick, enlisted soon after at Maclean on November 3.

While only a 20-year-old, Pa was accepted into the army, but said he didn’t lie about his age. The medical officer changed his papers to state he was 21, as he was such a healthy strapping lad.

At the Grafton enlistment, Hugh was among the first thousand to enlist and was given number 917. Patrick was number 1339. They were attached to the 15th Battalion and sent for training in Brisbane, Sydney and finally Melbourne, where they received their inoculations. The first two rounds of typhoid fever inoculations didn’t take effect with Pa though. He said they gave him a bigger (third) dose, which sent him unconscious (for three days) and straight to hospital.

Pa used to joke that he was the first casualty of the First World War and he was shot by an Australian doctor with a hypodermic needle!

When he was discharged from hospital, he was given a new number, 1495, and attached to the 8th Battalion, which embarked for war in February 1915, made up of mostly Victorian volunteers. His original 15th Battalion, which consisted of a lot of mates from his hometown along with his brother, had sailed two months earlier. This proved to be a potentially lifesaving event.

WAR

Pa’s 8th Battalion took part in the ANZAC landing on April 25, 1915, as part of the second wave at 5.30am. Ten days after the landing, his brigade (consisting of four battalions) was transferred from Anzac Cove to Cape Helles after the Turkish forces had annihilated the arriving British ships. Many soldiers were killed as they disembarked. Pa and his unit were sent to help the remaining British soldiers – he said there weren’t many of them left. His brigade assisted in the attack on the village of Krithia, which captured little ground and cost the brigade almost a third of its troops.

After Cape Helles, Pa returned to Anzac Cove to help defend the beachhead. He was part of the infantry and dispatched signals, but, as the casualties mounted, he was assigned the role of company stretcher bearer at the same time as Simpson and his donkey. By a strange coincidence, it is said that Simpson’s donkey was named ‘Murphy’ on the peninsula, as suggested in The Northern Herald (Cairns, Qld, Feb 6, 1919).

The role of stretcher bearer, which had a low life expectancy, was only given to physically strong men like Pa. Everyone knew ‘Simpson and his Donkey’, were sitting ducks, and Pa said they would ask each other, “Has Simpson got his yet?” Unfortunately, Simpson only survived three and a half weeks before being killed in the third Turkish forces attack at Anzac Cove on May 19, 1915.

Every day, Pa said he expected to die. He said “you had to be ready for an attack any second”, so they slept standing up in the trenches. The dead bodies were everywhere and each time someone was killed he thought: “Poor bugger. I’ll be next.”

In May 1915, Pa was wounded for the first time; he was shot in the head, losing several of his teeth and sustaining a shoulder injury. An officer asked if he was alright. Pa said, “Well, I’m alive.” The officer replied, “Then get back to it.” However, he needed medical attention and was taken to the make-shift hospital, where he witnessed, firsthand, the sinking of the ship, Triumph, by German submarine torpedoes on May 25, 1915. He said this disaster cast a gloom over the Anzacs – about the hopelessness and hell that they were now in, as well as seeing their mates in peril and being powerless to help.

While this event accelerated our troop’s hostility towards the enemy, an official Turkish report about the sinking of Triumph referenced their compassion, stating: “Turkish artillery with shrapnel shell could have easily blown up the rescuing boats, but feelings of humanity made us withhold our fire. The rescue work was unhindered, and the submarine escaped undamaged,” as reported in The Argus (Melbourne, May 29, 1915).

Pa said the Indians who came to Gallipoli (the Ghurkhas) were fearless and marvelous fighters. And he said the Turks weren’t so bad; he even came to like them during a ceasefire, swapping cigarettes and chocolates by throwing them across trench lines. However, he recalled the Germans would shoot anyone – the Germans shot Pa in Belgium, even though he wore a red cross showing he was a stretcher bearer.

Once, he left his post during a break in the fighting to find his brother Paddy. While they were talking, a shell came into the trench and killed two men beside them. Hugh ran back to his post, more terrified of being caught where he shouldn’t have been than his brush with death.

Pa fought throughout Gallipoli until the second last day of the Allied withdrawal in December 1915, including the battle of Lone Pine and Ari Burnu – nearly eight months of horror. He said that the retreating soldiers sprinkled a trail of flour along the paths and tracks they followed to the beach so they would not lose their way.

On December, 19, 1915, Pa was sent to Egypt and then, in March 1916, he and his battalion sailed for France and the Western Front. France recorded its coldest winter on record that year. Pa said: “You were up to your knees in mud.” The death toll in France was much worse than at Gallipoli. Pa fought at the Battle of Messines in June 1917 in West Flanders, Belgium. He said it was a “terrible place, with men shot standing up, bogged down in the mud in the trenches”.

Pa continued as a stretcher bearer during fierce fighting at Amiens, Armentieres, Bullecourt, Bapaume, Fleurs, Polygon Wood, Pozieres, the Somme, and Ypres. He was twice mentioned in dispatches and received the Military Medal for his actions during the Battle of Lys (Vieux Berquin) in April 1918.

The citation reads, in part: “Pte Murphy showed splendid courage and devotion to duty and carrying wounded men across the open from the advanced posts to the rear under very heavy artillery and machine gun fire. Though twice wounded he continued his fine work, refusing relief. During an enemy attack, which was preceded by heavy bombardment, he went from post to post across the open, dressing the wounded in each post. His conduct earned him the admiration of all ranks and devotion to duty was the means of saving many lives …”

He downplayed his bravery and courage; only commenting when asked: “I was just doing what I had to do, but that day an officer happened to see it.”

Pa’s brother, Paddy, ended up with trench foot in France in 1917 and was admitted to hospital a number of times. Pa said: “It was so cold that winter. I was lucky, my feet were good.” Paddy was granted ‘special leave’ to Australia, given by the A.I.F. for troops who had left Australia in 1914 and been in service for four years – they were referred to as the ‘originals’. Paddy set sail on October 8, 1918 for the long awaited journey home, during which peace was declared.

More than five years after he enlisted, Pa sailed back to Australia on January 14, 1919, disembarking on his beloved home soil on March 5.

On March 26, 1919, one of the largest gatherings ever recorded at a social function at Palmer’s Island assembled in the public hall to welcome home Hugh Murphy. Attendees included visitors from all parts of the lower river, including prominent residents of Maclean, Harwood, Chatsworth and Yamba. The Clarence River Advocate newspaper noted that Hugh “enlisted at the outbreak of the war and went through the fiercest of the fighting of both the Gallipoli and France campaigns, unscathed by the arms of the enemy”.

He was discharged in Sydney in August 1919. An officer told Pa that he was the longest active serving soldier at that time. The Certificate of Discharge states that he had a GSW (gunshot wound) which is usually accompanied by damage to blood vessels, bones and other tissues with a high risk of infection. He was offered an army pension but, despite being a gentleman who never used strong language, he told them to “stick it”, as he was so disillusioned.

POST WWI

Pa attempted to settle back into his previous life and went back into cane cutting, bought some racehorses, became secretary of the Yamba Race Club and was granted a bookmaker’s license. He met and married Margaret Duster in Lismore in 1924 and they bought the Mount Pleasant Hotel in Gympie, where they had four children – Patricia, Margaret, Kevin and Iris.

With the outbreak of World War II, Pa joined the Volunteer Defense Corps and held captain’s rank by the war’s end.

The couple retired to Brighton in Queensland in 1960. Margaret died four years later and Hugh lived alone until 1973, when, at 79 years of age, he married Katherine Holdway. Always the adventurer, Hugh and Katherine went on an overseas trip for a year-long honeymoon.

During his later years, Pa would become quite emotional remembering what a terrible waste the war was. He very rarely spoke about it; however, he remembered it clearly and woke from vivid nightmares every night until the day he died.

Two weeks before he was due to return to Anzac Cove for the 75th anniversary in 1990, as Queensland’s oldest Anzac at 96, Pa decided he could not return. He said: “I refused to go, for the reason that I never wanted to see the battlefields again. When you go through the first few months of Gallipoli, you never want to return there. I’ve seen so much heartbreak with the boys getting battered. I still get nightmares.”

Meanwhile, in Brisbane, the anniversary drew a large crowd. Pa was a highlight of the ceremonies and, after watching the dawn ceremony’s live coverage from Gallipoli, he said: “I thought it was magnificent. I’m very proud of the Australian generation. Very, very proud. They’re thinking of those that gave their lives, brave men, to the fallen, to the fellows that are left behind. May they rest in peace.”

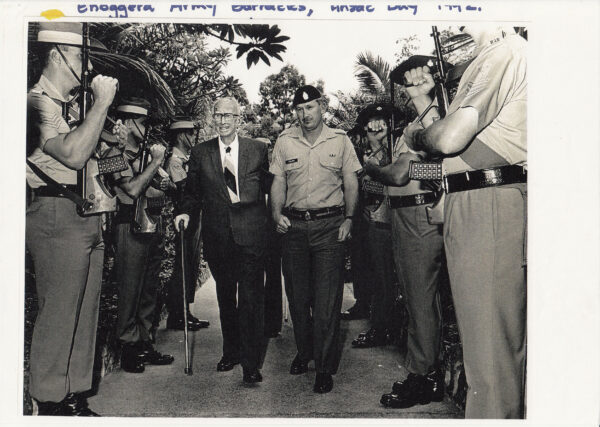

Pa attended his last ANZAC day parade in April 1993 and was on the front page of The Australian. He also visited the 6RAR Sergeant’s Mess at Gallipoli Barracks Enoggera, as the sole representative of the Gallipoli Legion.

Pa was a gentle soul who hated war, but every year he honored his Anzac mates who didn’t return. With tears in his eyes, he said: “It will never go out of my mind, every night I think of the boys, every night, and I get quite emotional when I think of what a terrible mistake it was, a dreadful mistake.”

Pa celebrated his 100th birthday in February 1994 with a military police escort to a celebratory mass and then a birthday party attended by over 200 people. Two sergeants in full ceremonial dress accompanied him throughout the day.

Sergeant Andrew Murphy (no relation) presented him with a National Flag “on behalf of serving soldiers today, yesteryear and the future”, a framed flag of the 6RAR Battalion and framed photo of the National Flag with the colour of his old 8th and 15th battalions underneath.

Mum said Pa “fought with courage. He survived and lived with courage. Aged 100 years, he showed us how to die with courage.”

Pa had always wanted to make the century. He died 13 days after his 100th birthday. He had held onto life, with its many and varied adventures, for more than one life time – some of the adventures led him into hell and back. Now, he can finally rest.

Note: Donna Morgan’s mother, Iris Morgan, supplied most of the direct quotes.

“I was only 22 when Pa died and, at that time, I didn’t value the importance of obtaining such specific and personal information,” Donna says. “I certainly do now that I’m older with a young family. The time, love and perseverance of my mum in documenting the details of Pa’s life over decades were crucial in telling his story.”