Thomas (Tom) Phillip Sheehan was born on 23 September, 1893, and apart from his war service, lived in Lawrence all of his life.

Like many children of those days, Tom had very little schooling, spending most of his time with his father, John, who was a well-known teamster, travelling with his team between Lawrence and Tenterfield.

Tom was one of eight children. His eldest brother, Con, joined the Light Horse and fought in Gallipoli, where he was wounded.

Tom, a fisherman, was 23 years old when he enlisted at Grafton on 18 January 1916, along with John Thomas Shaw, a railway guard from Lawrence. Tom was assigned to the 36th Infantry Battalion ‘D’, his service number was 1226. He embarked at Sydney on H.M.A.T Beltana 72 on 16 May 1916.

Tom was sent to France, spending three years there as a despatch rider. He served at Étaples which became the principal depot and transit camp for the British Expeditionary Force in France, and also the point to which the wounded were transported.

The military camp had a reputation for harshness and the treatment received by the men there led to the Étaples Mutiny in 1917. Étaples was also, from a later British scientific viewpoint, at the centre of the 1918 flu pandemic. There was a mysterious respiratory infection at the military base during the winter of 1915-16.

Tom suffered several minor wounds, and when he was shot through the leg in September 1918, he was hospitalised in France. He was shipped home on the “Orita” on in June 1919.

He was welcomed home, along with Sgt S Plater, by a large gathering at Pinegrove. The crowd had braved very inclement weather and incredibly bad roads to be present. Both men were presented with a gold medal. In October, 1917, the Maclean War Service League held another welcome home ceremony, and he, and nine other returned servicemen, were presented with medals by the mayor.

Tom’s service is recorded on the Maclean Public School Honour Board, the Mid and Lower Clarence Scroll and the Taloumbi District.

On his return to his civilian life, Tom worked as a fisherman and had an unsuccessful attempt at farming at Shark Creek.

When the 2NR broadcasting station opened in the mid-thirties, Tom was employed as a cleaner, gardener, and general handyman. In 1955, he collapsed at work and was taken to Maclean Hospital. Tom died later the same day. He was only 62 years old.

He was survived by his widow, his step-daughter, Marjorie, and his children, Phillip John, Noelene Margaret and Thomas Dixon. His daughter, Patricia had predeceased him.

All of the family was educated at the Lawrence Public School and the Maclean Secondary School.

Noelene later married Gordon Weeks, and they were founding members of the Lawrence Historical Society. Both were instrumental in acquiring the 2NR Broadcast Station to become the Lawrence Museum.

Remarks

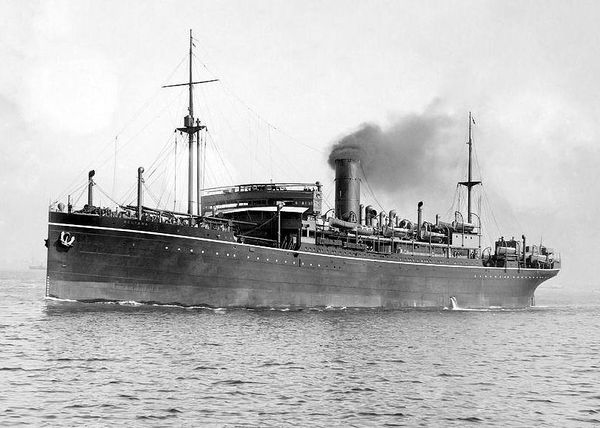

HMAT A72 Beltana

The ship was owned by the Peninsular & Orient Steam Navigation Co, Ltd, London and used on the London to Cape Town, Melbourne and Sydney route

It was leased by the Commonwealth until 14 September 1917 when her management was transferred to the British Admiralty. The Beltana made at least five journeys between Australia and Egypt or England.

In 1919, she resumed her Australian service via Suez, and in 1930 she was sold to Japan.

She was laid up and scrapped in 1933.

World War I

The railway, with its network of connections across the north of France, became of strategic importance during World War I, and it was added to temporarily during the period it lasted. Étaples became the principal depôt and transit camp for the British Expeditionary Force in France and also the point to which the wounded were transported.

Among the atrocities of the war, the hospitals there were bombed and machine-gunned from the air several times during May 1918. In one hospital alone, it was reported, “One ward received a direct hit and was blown to pieces, six wards were reduced to ruins and three others were severely damaged. Sister Baines, four orderlies and eleven patients were killed outright, whilst two doctors, five sisters and many orderlies and patients were wounded.”

The military camp had a reputation for harshness and the treatment received by the men there led to the Étaples Mutiny in 1917. Étaples was also, from a later British scientific viewpoint, at the centre of the 1918 flu pandemic. The British virologist, John Oxford, and other researchers, have suggested that the Étaples troop staging camp was at the centre of the 1918 flu pandemic or at least home to a significant precursor virus to it. There was a mysterious respiratory infection at the military base during the winter of 1915-16.

Private A S Bullock recorded in his World War I memoir entering Étaples with his battalion just after the armistice. The camp, he noted, was “almost infinitely expandable at very short notice”, attributable to its organisation in groups of huts, each of which contained a headquarters, a cookhouse, and a store housing numerous additional tents and equipment. Bullock also describes the military hospital, whose thirty or so inmates were all “murderers…at psychological war with one another”.

The nearby six-hectare Étaples Military Cemetery is resting place to 11,658 British and Allied soldiers from the conflict. When the war artist John Lavery depicted it in 1919, he showed a train in the background, running along the bank of the river below the sandy crest on which the cemetery was sited.

Following the war, the town was given recognition by the French state for the difficulty of accommodating up to 80,000 men at a time over four years according to Bullock “when full it could accommodate half a million men”and the damage done by the enemy bombing which their presence attracted; it was awarded the Croix de guerre in 1920.

Roz Jones