The story of the Nymboida coal mine is one that can be described as nothing less than extraordinary. It’s a tale of great mateship, rebellion, bravery, and tragedy. The actions of the mine’s workers are even said to have rewritten the industrial rules for miners around the world.

Josh McMahon recounts, with those who were there, the extraordinary events of the mine in the 1970s, which for surviving workers are still very much alive in their minds today.

Defying being sacked to instead take over the Nymboida coal mine was an ecstatic victory for its workers in 1975. But little did they know that this fateful decision had paved the way for a tragedy that would claim the life of one of their own, and prompt acts of extraordinary bravery.

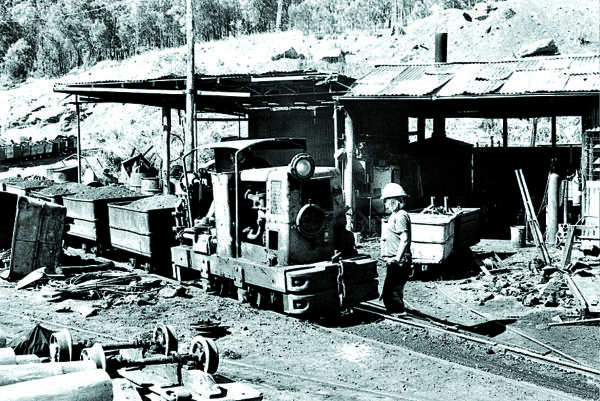

The blokes at the Nymboida coal mine knew what it was to do a hard day’s work. Unlike the rest of the mines throughout Australia, their underground operations remained completely un-mechanised. Each day, the blokes would scramble down low-roofed tunnels to ‘the pit’, where they would pick away at the coal face and shovel it into carts, often working in a space less than 30 inches high.

Highly explosive methane seeping from the coal seam was a constant threat to the miners. They monitored the deadly gas using a primitive lamp, as it couldn’t be detected by sight or smell. Methane would burn at the top of the lamp’s flame, alerting workers that levels had reached the point where the mine was classed as explosive.

Collapse of the narrow tunnels was also a never-ending danger. Propped up only with timber supports, these lifelines to the surface constantly threatened to cave in and bury or trap the workers.

Despite the horrendous conditions, the 30 or so blokes would extract 100 tonnes of coal from the mine each day.

But in February 1975, operators of the mine delivered a devastating blow to their Nymboida employees. Operations were no longer deemed profitable, and the mine would close, leaving the workers without jobs. According to the union, employees were also unlikely to receive entitlements of around $70,000 – a lot of money in those days.

The news left workers such as Ian Carter wondering what they would do next. He was married with a child and one on the way, and had also just bought a house.

“Everything goes through your head, wondering where your next dollar will come from – it was a real worry,” he recalled.

Likewise, the mine’s electrician, Neil McLennan, had not long been married and had also bought a house.

Workers met with union representatives at the Good Intent Hotel in South Grafton. It was at this meeting that an extraordinary decision was made: the men would refuse to take the sack.

So at 7.30am on the Monday morning, the men went back to what they knew best – extracting coal from the Nymboida mine.

Unable to sell the coal for an income, the union agreed to levy its members to pay the Nymboida miners a wage, and operations continued using explosives smuggled in from across the Queensland border. The workers were trespassing, but continued their ‘work-in’ regardless.

Two weeks later the mine operators withdrew the dismissal notices, only to reissue them a couple of days later.

This time when the men attempted to return to work, the mine had been locked up and equipment tampered with to prevent operation.

But it wasn’t enough to stop the determined coal miners from getting back to the job that was in their blood. A pair of bolt cutters solved the initial access problem, and Neil made short work of repairing the electrical switches. They were soon back to it.

The rebellion was thrust into the national spotlight, when it was publicised by television program A Big Country. The union used the publicity to leverage a deal to take over operations. To sweeten the deal, the union agreed to take on liability for the unpaid entitlements.

In effect, the men who were just employees of the Nymboida coal mine became its owners. According to the union, it was an international first, and the action had rewritten the industrial rules for miners around the world.

Ian, Neil and the other men worked hard, knowing that regaining their lost entitlements depended upon them making the mine productive and profitable. They once again returned to selling their product to their sole customer, the Koolkhan power station. Defying the odds, by the end of the year the workers had returned the mine to being a profitable operation.

But then, on Monday January 12, 1976 – the first day back after the Christmas break – disaster struck.

It was right on knock-off time, Ian recalled, and he and a number of other blokes had made their way to the top ready to go home. Suddenly, there was a flutter of wind from the tunnel, and the coal carts clattered against each other.

“At the time I didn’t know it was an explosion – I thought it was a roof fall,” Ian said. “I was only in my late 20s and didn’t know a lot about explosions.”

Ian and another bloke, Frankie Smidt, made a decision that they would go down into the mine to make sure no one was trapped.

“We looked down and there were three lights coming up. We met up with them and they said it was a shot-firing explosion. They’d been hit by bits of coal and they were bleeding a bit. They mentioned there’s another bloke further in, trying to get out,” Ian said.

Ian and Frankie continued down another 60 metres or so, and discovered Tommy Ford crawling up the tunnel.

“He had skin off everywhere. He had an awful experience, went deaf in one ear,” Ian said.

The pair dragged their mate to the surface, where he was rushed away by ambulance. Tommy survived, but never went down a mine again. He later died in 2009.

Meanwhile, mine deputy in charge at the time, Neil McLennan, had been told there was still one man down the mine. Neil phoned manager Jack Tapp, and Jack rushed to the scene. Attempts to recruit a rescue team were met with the heartbreaking news that such a team would take several days to assemble. Not prepared to wait, Neil, Jack and Frankie decided to enter the mine and attempt to undertake a rescue themselves.

“It was up to us to do what we could. Simple as that. So the three of use went down,” Neil said.

Admittedly “a bit scared”, Neil descended the treacherous tunnel, fearing a second explosion could rock the mine at any time. He knew the tunnels well, however, and believed he knew where the missing man would be.

The three came to a particularly narrow section, and Neil decided to continue alone. He crawled another 30 to 40 metres, where he found Graeme Cook.

“I crawled in there and found him sitting there like nothing was wrong. Just sitting there. Not a mark on him. But he was dead,” Neil recalled.

They were met by Neil’s older brother Trevor, who had brought two police to the site. Graeme had been working at the mine just 10 months, before it claimed his life.

Graeme’s lifeless body was then carried to the surface.

It’s an experience that still haunts Neil today.

“But there’s not much you can do about it … you’ve just got to learn to live with it,” he said.

An inquiry into the incident exonerated the workers from any liability, according to the union. Neil said he believed Graeme’s inexperience had been a factor in the disaster.

Saddened by the tragic event, the men continued, nevertheless, to work the mine until 1979, when the mine’s only customer, the Koolkhan power station, closed. There was no longer anyone who would buy the coal, despite its renowned high quality.

Despite the news, the men had earned all of their entitlements owned to them. Some retired, some moved to other areas to find work. Trevor and Neil relocated to the Hunter Valley to work at a modern, open cut mine. They continue to work in mining in the Hunter today.

Ian, Neil, Trevor, Jack (now deceased) and Frankie were this year named recipients of the NSW Governor General’s bravery citation, for risking their lives to help their mates.

The extraordinary tale also inspired a documentary, Last Stand at Nymboida, which has now won a total of 12 international film awards. The film was written by Labor movement journalist Paddy Gorman, with award-winning film-maker Jeff Bird. Paddy also took on the executive producer role, while Jeff directed the film.

It includes interviews, footage, and images both new and old, exploring the history of the mine. For more on the documentary, visit www.nymboidadoco.com.au

This article was originally published in Clarence Scene magazine in 2012.